Iwate and Fukushima Prefectures were desolated by the 2011 wave that encouraged a devastating atomic catastrophe. Presently, this shocking, boggling area is inviting voyagers back.

Trust spiraled delicate as a rice shoot along the restored Sanriku Rail route Rias Line in north-eastern Honshu. Summer’s sprouts spilled from pots on station stages; storybook houses peeped from the timberlands’ creases; a man bowed next to the ice-blue stream and purified a fistful of spring onions. Rice crops blazing by in the valleys were ready for the collection: their majestic yellow sparkle filled the windows as my companion and I shook along this once-doomed shoreline.

On 11 Walk 2011, networks along the northeastern seaboard of Japan’s greatest island, Honshu, were cleared from their moorings when a seismic tremor estimating 9.1 on the Richter scale encouraged a wave of fantastic extent. Seawater barrelled into the saw-toothed coastline, improving the foundation, clasping backwoods, and flushing lives from each hole. At the point when the sleek tide subsided, close to nothing yet fragmented debris remained.

Such destruction is recognizable to this nation situated on a separation point; the archipelago country has persevered through an excessive number of catastrophic events to recall – most as of late, in January 2024, a 7.6 size tremor in the Noto Promontory in Ishikawa Prefecture. Be that as it may, recognition is the custom by which the Japanese get a handle on their destiny. In Honshu, a reason-drawn map separates the various “catastrophe dedication offices” strung out along the 500km stretch of shoreline impacted by The Incomparable East Japan Seismic tremor and Tidal wave of 2011. Clouded from view underneath the railroad line are cairns raised before ages to caution of nature’s savagery.

“Try not to fabricate homes underneath this point,” peruses one engraving. “Regardless of how long has passed, be ready for torrent.”

That unstable sea was an ocean of quietness as we meandered northwards from the city of Kamaishi to Namiitakaigan, a shoreline village four hours north of Sendai in Iwate Prefecture. Here, blossoms followed from the bungalow gardens adjoining Namiitakaigan Station; a cenotaph 266m uphill from the ocean side was circled with Japanese content: “This is where the wave came to.”

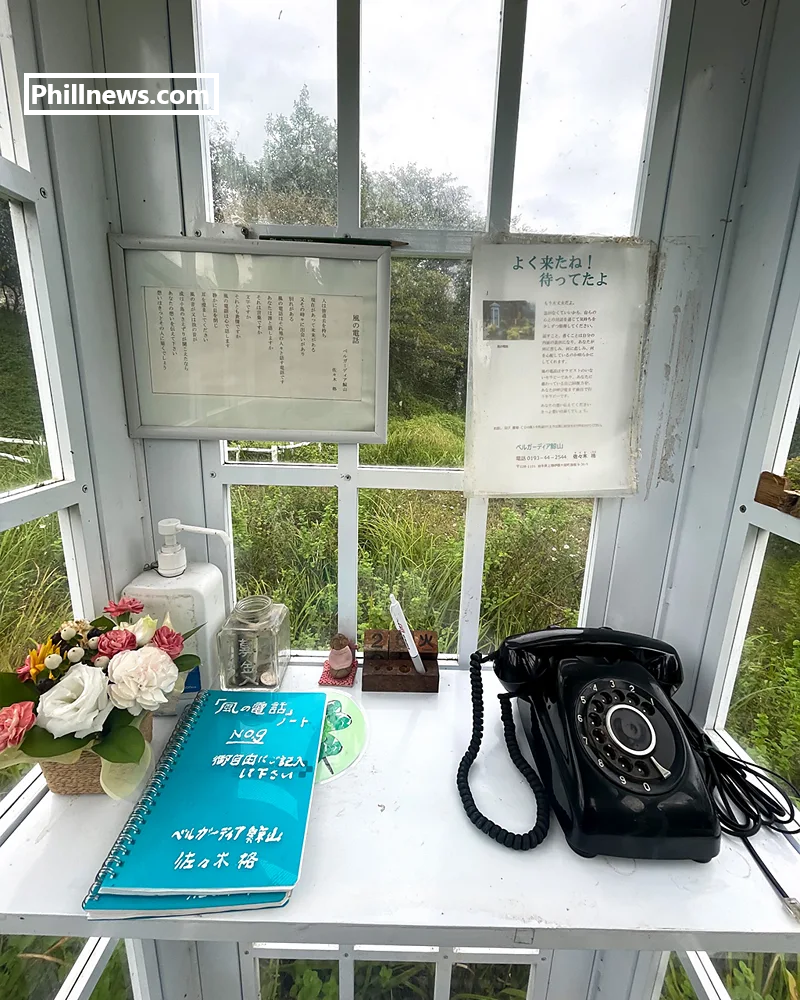

We’d been drawn here by a story: in a delightful nursery on a close-by slope stands a telephone box where individuals cooperate with the dead. Before the fiasco, Namiitakaigan occupant Itaru Sasaki made a figurative association with his late departed cousin by setting a detached phone inside an English-style telephone box. Here, he made sense of a 2016 episode of This American Life, he could address his cousin, and his considerations “carried on the breeze”. As accounts of Sasaki’s custom spread, those impacted by the wave – and different misfortunes – showed up to look for their comfort on “The Telephone of the Breeze”.

However great many individuals have trampled the way to Sasaki’s nursery, we were its only guests that day. Birds fluttered between foamy crepe myrtles and maple leaves gradually evolving variety; it was a strong setting wherein to ponder misfortune: so electric with life, so hauled with distress. I shut the telephone box entryway behind me, lifted the recipient, and quietly communed with the friends and family I’d lost.

The mindset lifted coming back into town: we met a lady pushing a cake truck from one way to another and purchased two of her custard-filled doughnuts.

“Oishi! (Flavorful!)” we expressed, skirting down the slope.

Yet again recycled memory pounced upon us out and about prompting Minshuku Takamasu, our housing for the evening: “Torrent Immersion Segment,” a sign said. However, owner Yasuko Nakamura’s face was wreathed happily as she invited us in. Just the top of her raised ryokan was harmed by the wave, she imparted through motions and an interpretation application and my companion’s corroded Japanese.

“I was at my home in Trono [an hour’s drive inland] when it came,” she said.

What’s more, however, unfamiliar visitors are currently interesting, Nakamura was occupied enough with her drawn-out tenants: secondary school guests, an angler jumper who made his living from the inlet, a developer chipping away at the reproduction of the close-by town of Otsuchi, which we’d went through on our way here. A big part of its residences and a large portion of its business properties were cleared out by the wave. The manufacturer’s endeavors would assist with making Otsuchi more grounded, he said, as Nakamura served the products of that once-wrathful ocean for supper: wakame (kelp) salad, barbecued saba (mackerel), miso stock weaving with a delicious yet vague fixing.

“What is it?” I composed her application.

“It’s made by working fish,” she made sense of, her Japanese content blossoming as effortless as the kaiseki bowls she’d laid before us.

The angler jumper, we learned, claimed an apple plantation in his home prefecture, Aomori. It snowed a great deal there, he expressed, moving out from a fanciful float. Benevolently he wasn’t plunging off Namiitakaigan when the tidal wave expanded forward. We shivered all in all at the idea: there was a compelling reason to decipher such envisioned fear.

The next morning, we acknowledged a keepsake from Nakamura: gently painted containers loaded up with purpose.

“Popular purpose, from Kamaishi,” she said.

From Namiitakaigan, the train thundered south along a shore lapped by delicate waves. It was difficult to accommodate this scene with the pictures of 2011, when railroad burrows overflowed, supports clasped and Koishihama Station was washed clean away. Presently, scallop shell wreaths spilled over from a niche on the station’s reproduced stage; a gathering of pre-schoolers landed here with their educators and joined their shell-decorated flag to the sanctum.

“A request,” said a lady on the train who had intuited the inquiry in our eyes.

Be that as it may, rudimentary accolades before long changed into rich praises. At our next stop, Rikuzentakata, the Hiroshi Naito-planned Iwate Tidal Wave Dedication Gallery stopped the coastline like a splendid white gravestone. The sky moved on the pool of reflection through an opening in the patio roof; in the wings beginning it, we heard survivor declarations, watched media shows, considered objects recuperated from the downpour: a folded fire engine, a youngster’s mud-splashed console, a bus station collapsed like origami. Recognition gave way to profound appearances in the shows tending to regulatory weaknesses, illustrating alleviation systems for future debacles, and offering thanks for the world’s amazing overflows of help and distress.

“It is shrewdness passed down to people in the future,” said guide Satoko Kinno.

We had a transport to get, yet Kinno encouraged us to climb the seawall sitting above the fledging woods bordering the inlet – a swap for the extremely old pine ranch that once braced the city against the sea’s impulses. The Wonder Solitary Pine Tree was the ranch’s last one standing. In any case, mortally harmed by saltwater, it passed on in 2012; was it polished off by anguish, I pondered? Presently safeguarded with synthetic substances and upheld by a steel bar, this landmark lingered over the leveled scene, a strong image of strength. Close by, the tidal wave ran remains of Rikuzentakata Youth Inn slouched over a lake grieving their appearance.

From the seawall, we glanced back at the gallery, which from this point seemed to have been cut from the bedrock. The show-stopper was enveloped in the clean green skirts of Takata Matsubara Torrent Remaking Dedication Park.

Past it, Rikuzentakata emerged once more from the slurry.

The rail line south of the city – destroyed, as well, by that mass of seawater – was all the while anticipating fixes. We got the substitution Transport Fast Travel (BRT) to Kesennuma, and the train onwards to Sendai. Here we boarded an unfilled carriage on the JR Joban Line headed south for Fukushima Prefecture. Until a couple of hours sooner, we had no clue about where we’d remain that evening. Inns were inadequate along this course, and the shoreline it crossed was still troubled by the aftermath of the tidal wave set off atomic fiasco.

Murkiness had fallen when we showed up at Haranomachi Station. Not a spirit wandered the roads. The lacquered exterior of a ramen bar gleamed red, yet all at once nobody blended inside. We purchased sandwiches from a 7-Eleven and withdrew to our room at Inn Areaone Minamisoma, which appeared to be deprived of different visitors.

More like this:

• The Michinoku Beach Front Path: Japan’s new 1,000km way

• Japan’s adored sluggish movement train

• Another night train interfacing a portion of the landmass’ incredible urban communities

Like brought by us, a bus transport was holding up external the station the following morning at Futaba, found near the site of the atomic mishap. Radiation levels here are said to have gotten back to business as usual. Splendid wall paintings streamed across the cluster of structures remaining in an area of town recast as “Futaba Workmanship Region”. Sections of land of no man’s land spooled by as the transport driver directed us towards The Incomparable East Japan Quake and Atomic Fiasco Remembrance Exhibition hall. There it remained amid an ocean of void parcels: a pale building of Cubist extents – a trinket, maybe?

However, shockingly it was overflowing with guests, generally secondary school understudies on journeys. I noticed them engrossing, wide-looked at, occasions they were too youthful to even think about recollecting. Then I gazed for quite a while at a model propelled by the Fukushima Development Coast Structure, an initiative focused on restoring a modern base in this demolished district; it portrayed Futaba reconstructed as a “city representing things to come”: lavish farmland, energetic roads, an ocean side loaded up with holidaying families.

“It’s developing bit by bit,” said guide Kenichiro Hiramoto. “Just 70 or 80 [residents have returned] to Futaba Town, however they attempt to arrange their local area. Presently the pattern is rookies, youngsters – and the district upholds them.”

We will visit this city representing things to come 20 years thus, promised my companion and me on the train to Iwaki, over two hours south of Futaba. However gravely harmed by the torrent, the city has bounced back. After supper that evening we slid into a storm cellar bar, Tunnels, similarly as it was shutting. Proprietor Kazuya Hanazawa consented to blend two last mixed drinks. Shaking, blending, cutting wedges of lime, he regretted the many Iwaki inhabitants lost to the wave. He burned through a half year a while later aiding mop up, and made his bartop from wood rescued from the destruction.

“Japanese are exceptionally intense,” he said, squeezing his clenched hand to his heart. “I needed to make where individuals could feel much better. It’s a little [start], however, individuals from everywhere – Okinawa, Hokkaido, Japan – are all approaching back to Iwaki.”

Hanazawa put our mixed drinks before us: vodka creations effervescing like sunlight in the melancholy.

“Kanpai (Cheers),” we three said.

Phill News Entertainment – Phill News

Phill News Entertainment – Phill News